Eyes Watching and Other Work, 2021. Art Mûr, Montreal, QC

November 11 to December 18, 2021

Text by Paule Mackrous

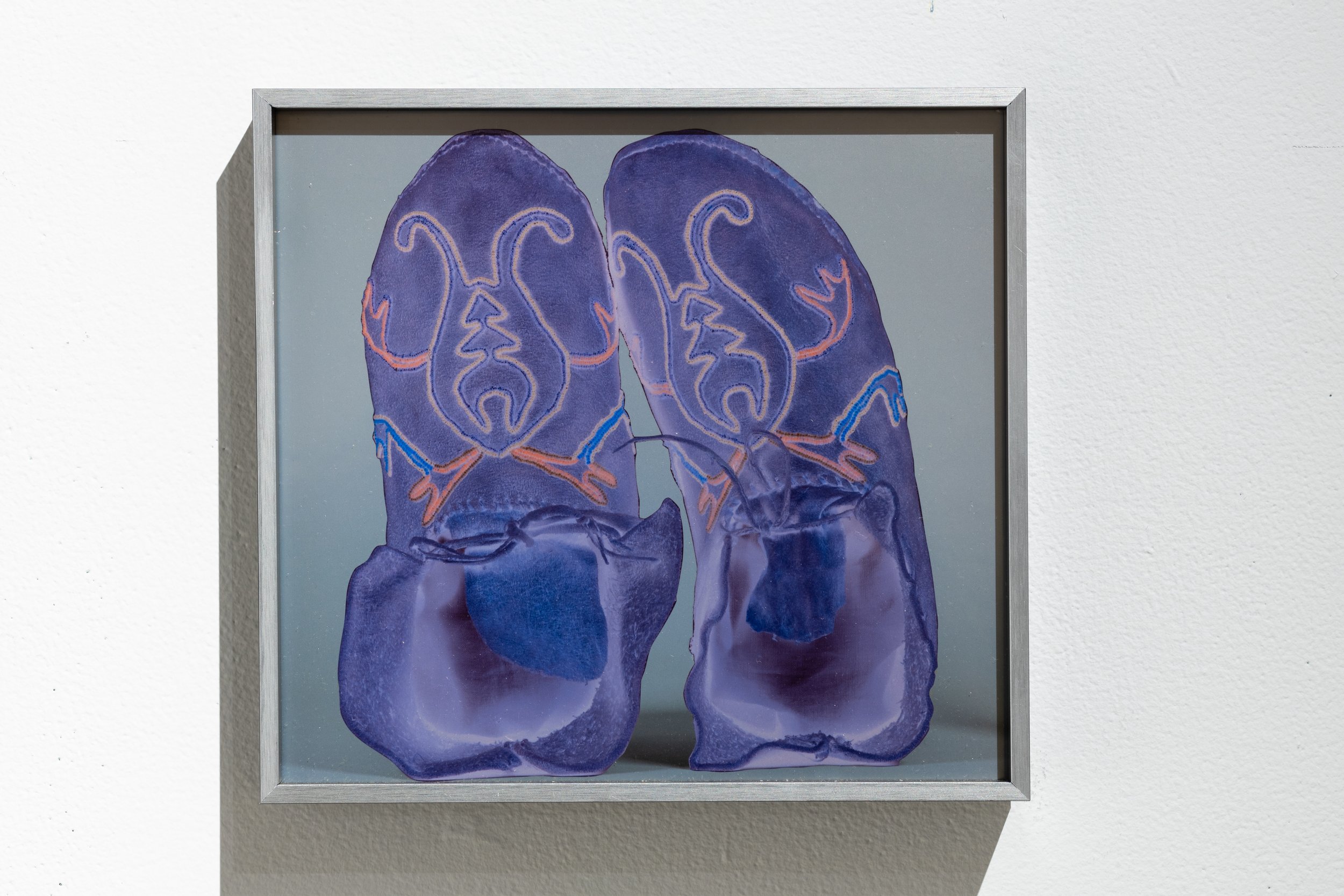

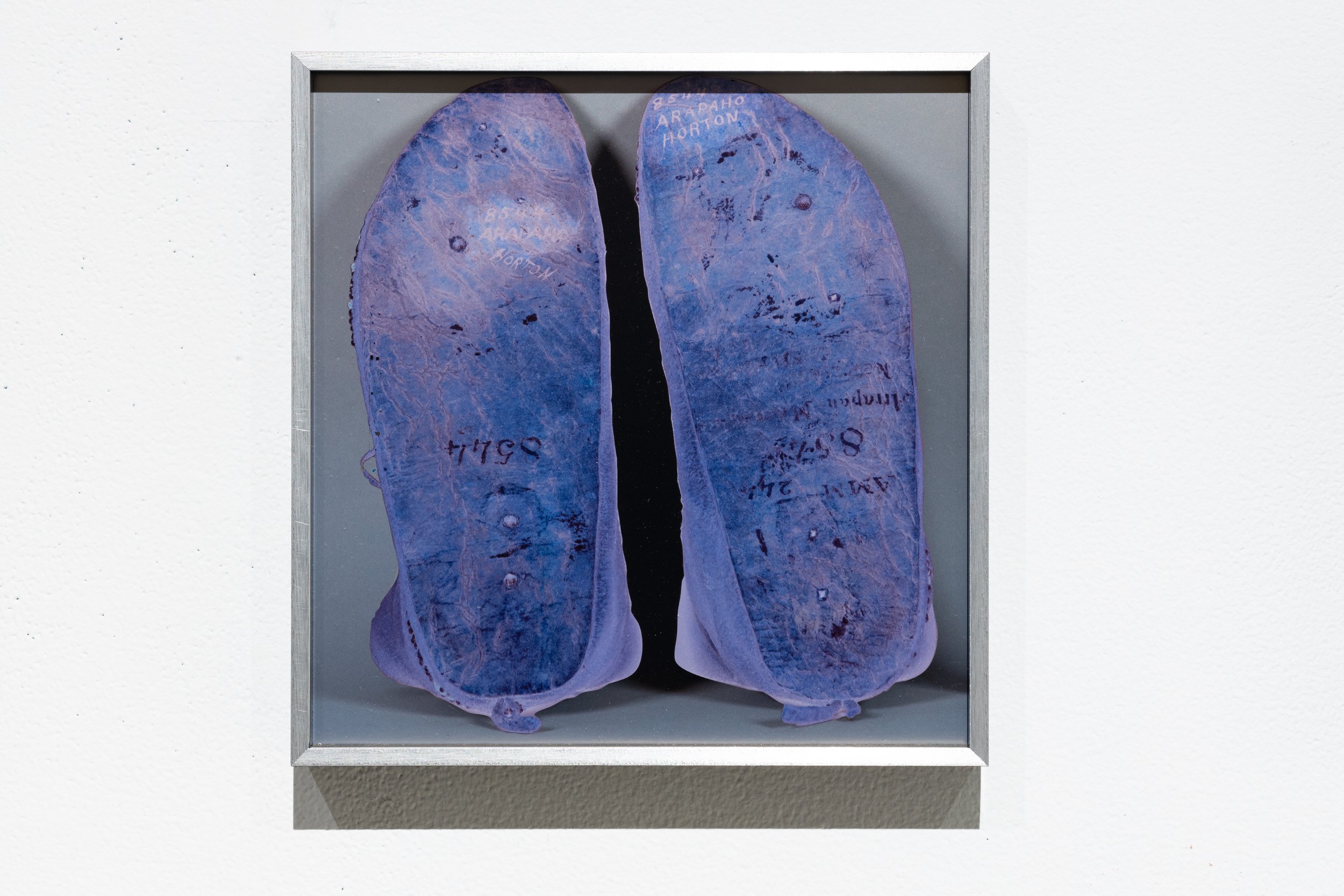

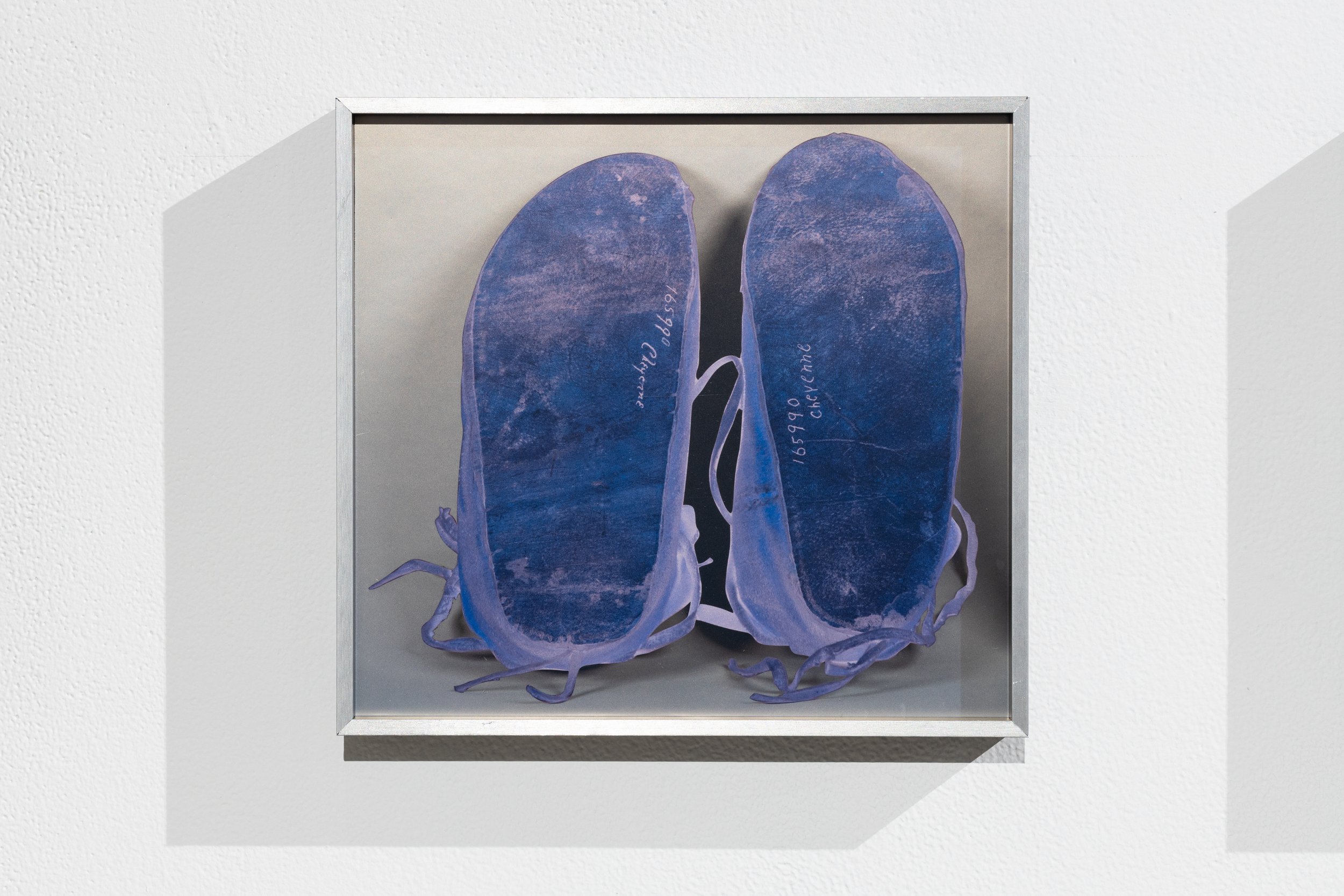

Artist of Algonquin origin, Nadia Myre is renowned for her work on the identity and history of Aboriginal communities. Practicing what André-Louis Paré so rightly calls “symbolic reparation”1, Myre once again challenges history, this time through images of moccasins from the collection of the Smithsonian's National Museum of Natural History. These are cropped and then digitally retouched. Can we speak of a practice of appropriation as we have done since the New Realists? The term would lack accuracy and, above all, justice. Here we recover something that has been torn from its meaning, from its culture and which points to a still current reality: that of thousands of diminished, stolen, mown down lives.

The photographed moccasins are arranged vertically, toes up. Impossible not to see the presence, beyond the images, of the people who wore them. We immediately see these imaginary people lying there, evoking in the same breath the colonizing genocides, the many "stolen sisters"2 and, more recently, the bones of hundreds of children buried near the residential schools of Western Canada. in 2021.

The inversion of the colors operated by the artist reveals a purple specific to the Wampum, these necklaces and belts of pearls cut in the mother-of-pearl of clam shells. This sacred object played a crucial role in the signing of Treaties, agreements between First Nations and white people regarding the disposition of land. The Wampum offering meant: “From the depths of the ocean this agreement abided by”3. The word that was to be consolidated by the Wampum was betrayed and the promised lands became, in many cases, stolen lands. The Wampum is also offered to one's neighbor to console him ("to wash away the tears" 4) when a loved one dies. Now, the moccasins floating in a neutral and greyish space, an aspect of the original images that the artist has preserved, reveal individuals who are measured in numbers, in statistics, much more than in intimate lives belonging to a community. By collecting cultural elements, the institution inevitably contributes to the disappearance of the cultures it folklorizes, relegating their sovereignty to the past.

The images seem equipped with infrared sensors, as is done for masterpieces in order to reveal the processes, the drippings that led to the final version. The archive is thus unveiled as Foucault defines it: a structure of power in which the documents are ordered in a particular way limiting the possibilities of what can be said about them and, at the same time, the possibilities of "knowing" them. -even5. A photograph of a scale accompanies the series of photographs and indicates the need to operate a counterweight, in order to open up, at the very heart of the archive images, a space that generates other sensibilities and other discourses that carry them the beginning of a real reparation.

1. André-Louis Paré, “For symbolic reparation through art”,

Le Devoir, March 6, 2018.

2. The expression is borrowed from the book on Indigenous feminicide: Emmanuelle Walter, Stolen Sisters, Lux, Montreal , 2004.

3. Alain Ojiig Corbière, The Underlying Importance of Wampum Belts, March 30, 2015: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wb-RftTCQ_8

4. Idem

5. Baron, Jamie. (2014). The Archive Effect. Find Footage and the Audiovisual Experience of History. New York: Rootledge, P.13

https://artmur.com/wp-content/uploads/brochures/vol16_numero5.pdf