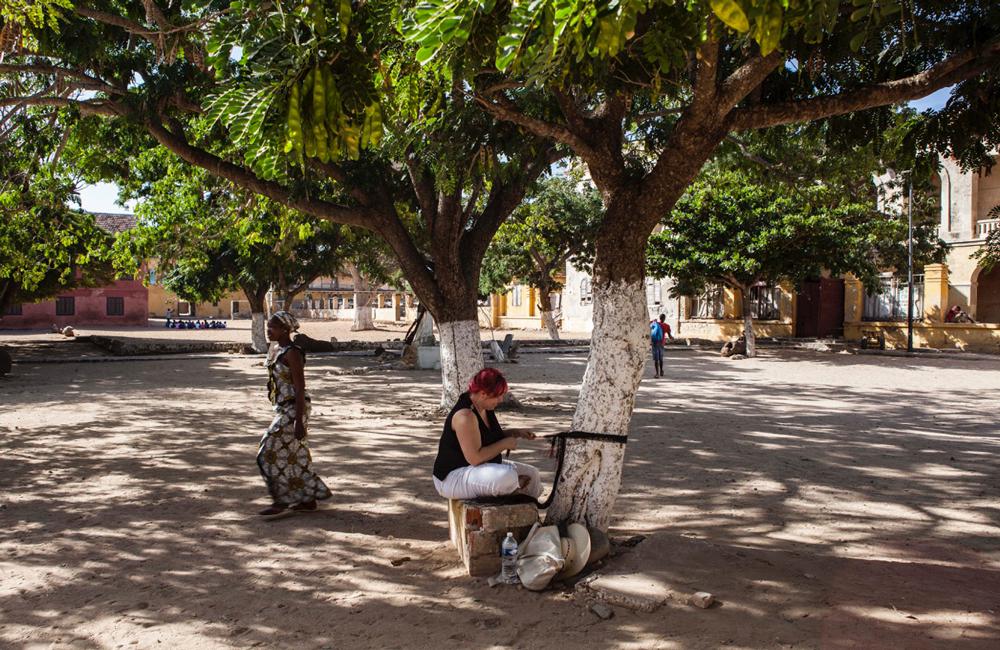

Nadia Myre at Work as part of the "Formes et Paroles" exhibition residency on Gorée Island, Senegal November 2014. Courtesy Musée Dapper, Paris. Photo Aurélie Leveau.

On November 19, in front of a packed audience at the Winnipeg Art Gallery, Montreal-based artist Nadia Myre was named the winner of the 2014 Sobey Art Award. It was the culmination of a whirlwind month for Myre that saw her jetting from the opening of a solo exhibition at Oboro in Montreal (which closes on December 13) to a two-week production residency and exhibition in Senegal and then directly to Winnipeg for the installation of The Scar Project (2005–13), her award-winning contribution to the Sobey exhibition at the WAG (which is on view until January 25). It’s a schedule that suggests the hectic pace of a contemporary artist in demand. But as I found in spending time with Myre in Winnipeg, she remains refreshingly down to earth and focused on a practice that puts the critical power of art in the hands of everyday collective engagement.

Now back in Montreal and with a bit of time to let the excitement of the past few weeks sink in, Myre has taken time out to answer some questions by email. Here, she discusses the end of The Scar Project, the legacy of an 18th-century Montreal slave that has made its way to Senegal, and the importance of keeping open ears and open minds.

Bryne McLaughlin: The Scar Project was a huge, even monumental, endeavour with contributions by more than 1,400 people from Canada, the United States and Australia gathered over eight years. I’m wondering what, for you, are the key points of consideration that surface in the work, particularly in the installation that is part of the Sobey award exhibition in Winnipeg?

Nadia Myre: The key points that surface with this project are our collective experience of the scar as personal and universal symbol. Each scar canvas and its accompanying story is unique and tells an individual narrative, yet bringing them together in an installation serves to highlight common threads of experience—hurt, healing and forgiveness.

As an artist I seek to draw out associations between these stories and the marks that represent them by arranging the canvases formally and conceptually. Even the barest, faintest, almost invisible marks, juxtaposed against the complete destruction of the canvas and its repair, are gestures that stand in for words. As the arrangement is both about the global and the individual and is recreated in each new installation, the associations I make are an ever-changing puzzle.

BM: Your Oboro show, “Orison,” which closes on December 13, marks a coda of sorts for The Scar Project. The multi-media installation, as you write in the exhibition text, is a “personal response to having carried The Scar Project—and its heartrending stories—for the last nine years.” Can you say a bit about the specific approach you took with “Orison,” particularly why you felt it was important to incorporate sound and image with sculptural elements? Is there resolution in the results?

NM: Sound is a crucial element in this work, and is increasingly becoming an important part of my practice.

I have been working through the symbols in The Scar Project for a long time. For instance, with the series Scarscapes I beaded the most recurring symbols found in The Scar Project‘s canvasses, creating digital photography from those beaded works. Now, I am working with narratives. The introduction of sound in “Orison” lets the stories from The Scar Project exist in a new way. Combining the voices in a five-channel soundscape allowed me to give the stories movement through editing and spatial placement, enticing the viewer to move through the installation. We hear vibrato in the voice that trembles, silence in the voice that pauses on the telling of difficult things, and I believe that resonates with the listener.

BM: You came straight to Winnipeg for the Sobey announcement from installing a new site-specific work for the exhibition “Formes et Paroles,” on Gorée Island in Senegal as part of the 15th Summit of La Francophonie. The work you presented there was based on the story of an 18th-century black slave in Montreal, known as Marie-Joseph Angélique, who was wrongly (or not; the historical debate has it both ways) accused and convicted of setting a fire that burned down a large part of the city in April 1734. What initially drew you to this story and in what ways did that story and the work you created from it in Senegal—on view until March 2015—relate to the context of Gorée Island?

NM: Gorée Island is known for the “Door of No Return,” a memorial at the gateway to the Atlantic slave trade. As the only artist from the Americas invited to participate in this exhibition, I wanted to explore Montreal’s slave history and share it with the people of Gorée, metaphorically bringing a story “from the New World” home. In my research I was surprised to realize how many slaves there were in New France—Native American, African and indentured Europeans…. I don’t remember learning about it in school.

In this work I am addressing the question of resistance that Marie-Joseph Angélique in Montreal shares with Gorée Island. Even though Marie-Joseph is a particular woman, in a particular city, the story resonates globally. Stories of resistance tend to elicit more stories of resistance. The work was really well received in Sengal and many people came forward and shared with me. I am always moved by these exchanges. At Gorée Island this also happened in a material sense. Across the Ocean is crafted using traditional fishing-net techniques. While I was on the island making the net, fishermen would stop and talk with me and share their expertise. One man, named Adaman, worked with me for several days.

I have been working on making nets for over a year. I learned the technique in Mashteuiatsh during a residency organized by Sonia Robertson. I was drawn to it immediately and ever since I have been carrying the idea of net-making as a universal language. Six months later in Mexico, while working on a land-art piece for the Cumbre Tajín festival, I watched fishermen at work and learned from them how to cast a circular net. Making and using nets can be dropped anywhere in the world and people will be familiar with it. All these experiences influenced “Orison” at Oboro, where a round net rises and falls like a body breathing.

BM: There was a palpable emotional charge at the Winnipeg Art Gallery when the envelope was opened and you were announced as the 2014 Sobey Art Award winner. It’s a win that was obviously well judged on the basis of your work. But I think that particular emotional charge also had a lot to do with the fact that this was the second year in a row (Duane Linklater, who made the announcement, was the 2013 award winner) that the top prize has gone to an Indigenous artist—yet another signal of the renewed emergence of a smart and strong Indigenous voice as a driving force behind the national contemporary-art dialogue. Is this true, in your opinion? How do you feel about the reward, and the responsibility?

NM: The voice that received the award is many. I am so grateful to have my work acknowledged by this award as a woman, as an Anishinaabe, as a mother. I think any artist will tell you it takes true grit to be an artist and to have lasted this long doing it. I look forward to the next 20 years.

As far as the “rising” Indigenous voice is concerned, I feel it has always been smart and strong. It is not new and I have had many role models. The difference might be in how this voice is heard and acknowledged today. Hopefully that listening will continue in all directions. I feel an ongoing responsibility for all of us to listen to each other and make space for one another, something that I actively pursue in my work.